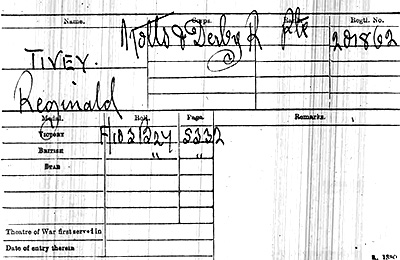

| Reginald Tivey was born 20th July 1896 in the

market town of Melbourne, Derbyshire. He was the middle child

born to parents Samuel Tivey, a shoemaker, and his wife

Elizabeth Smith. He was the biological brother of Harriet

Elizabeth (Bennett), Ernest William, Flora (Moore) and Samuel

who died in infancy. Reginald was brought up by the Singleton

family (William & Mary Ethel) and considered their daughter Lena

Molly Singleton as a sister. Reginald married twice - firstly to

Barbara Annie Bell Irving with whom he fathered a son Alastair

Michael, and later to Mildred Lydia Arnold Chappell . Special

thanks to Alastair for all the information that he kindly

donated to the site including the many photographs, artwork and

stories of Reginald's life. |

The following narrative is

by Reginald's son. "After the outbreak of World War I, in August

1914, Reginald enlisted with his local regiment, the Sherwood

Foresters – even though he was only eighteen, and the minimum

official age for service was then nineteen. He spent the first

two and a half years of his service in training, while his

regiment was held in reserve, apart from a brief distraction in

Dublin in 1916. It was at Easter in that year that the Irish

republicans chose to mount an uprising against the English, and

the regiment was sent over to help restore order. In a tragic

episode in the streets of Dublin, a whole detachment of

Reginald’s comrades were massacred in an ambush by Sinn Fein,

who were using guerilla tactics. Reginald never forgave the

Irish for that. His regiment remained in Dublin for a while,

continuing with their training, until things cooled down. Early

in 1917, Reginald’s regiment was sent to France to join the main

British front line. A major onslaught started in March. The

regiment passed through Foucocourt and the ruined villages of

Jeancourt and Vraignes, and pushed the Germans back 20-40 miles,

only to lose ground again when the Germans started a last,

desperate counter-offensive. At the beginning of April, eight

hundred of the regiment were in action again between St. Quentin

and Péronne on the Somme when another great advance started. As

a result of bad planning and organization, they reached the

enemy six hours late – instead of two hours before daybreak, as

intended, only to be mercilessly mown down by the German machine

guns, which the artillery were supposed to have silenced first:

out of the original eight hundred, only twenty-five were left

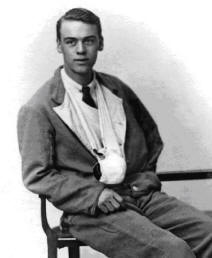

fit enough to carry on. Reginald was badly wounded in the left

shoulder, and was fortunate to get home. Indeed, at first he was

not expected to live. He was taken first to a dressing station

and then to a casualty clearing station at Bray-sur-Somme,

before being transferred to a hospital at Le Havre. From there

he crossed the Channel in the hospital ship “Lanfranc” (which

was sunk on its next crossing), before spending three years in

Springburn Red Cross Hospital and then Kelvingrove Red Cross

Hospital (now the Western Infirmary), both in Glasgow. He lost

the use of his left forearm and hand (which was ‘set’ as a

closed fist), for which he received a War Disability Pension for

the rest of his life. His industrial career was at an end, as he

could now only do clerical work; but surprisingly, neither his

sport nor his art suffered noticeably – and he could still play

the piano with one hand and a fist! The bullet that wounded him

was mounted by Mappin & Webb in London , and is inscribed “4.4

RT 1917” (The 4.4 refers to the date of the action). When he

visited the War Memorial in Melbourne in 1975, he was genuinely

moved to read all the names of those killed in France, with whom

he had been at school or played games in his youth; there were

so many of them, almost a lost generation. Commentary by

Reginald's son. Many thanks to him for the amount and the

quality of the information received with regards to Reginald and

the Tivey Family of Melbourne."

|